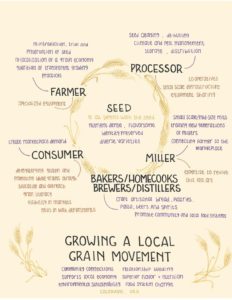

A local sustainable food ecosystem needs a full marketplace to really thrive. Farmers, who grow things beside mass market commodities, need a processor to sell their product to, ideally locally. That processor needs to transform the product into a wholesale or consumer product, ideally sold locally.

Developing that cycle creates a local food economy and it’s something the Colorado Grain Chain, a nonprofit with a mission to develop a local grain economy, hopes to jumpstart. Owner of the stand-out local bakery Moxie Bread Co., Andy Clark, chairs the org and local miller Michele Moffat serves as treasurer.

(Moxie Bread Co. opened a milling operation this April with a mission of creating a market for locally grown heirloom grains, buying wheat from farms like Aspen Moon and milling it into flour to make its popular bread and pastries.)

Michele runs Freshly Milled where she mills heirloom grains into flour. Around the same time that Moxie Bread Co. got its mill this spring, Michele installed a traditional stone mill, which she purchased last October — a refurbished 1995 30-inch Meadows Mill which lives at Erie Airport in an aircraft hanger zoned for light industrial use.

Michele grows her grains on an acre-and-a-half of the 30-acre farm she owns at Nimbus Road and 75th Street in Longmont, around the corner from Browns’ Farm. She sells the flour she mills through a couple CSAs, such as Browns’ Farm, as well as her website. Michele also sells and donates to Denver’s Metro Caring food bank, which has quadrupled its demand since Covid.

While she currently mills grain she has purchased, Michele has sent her own wheat out for testing and if it comes back with a good profile, she will mill it and sell it under the Freshly Milled brand.

At her Longmont farm, Michele also grows alfalfa and hay, which John Schlagel manages. John has stewarded the land for years, even for its prior owners, and farms over a thousand acres on his own in the county between land he owns and leases.

From grain to consumer

A hundred years ago, many towns had a mill house and the whole endeavor required community collaboration, Michele told BLDRfly — from tilling, planting, using a combine to cut and thresh the wheat, cleaning the seeds, and milling it into flour.

“There’s something about wheat growing that either requires scale or equipment sharing,” says Michele. “It requires capital investment and real estate on where to put it. That’s something the grain chain is trying to help facilitate; like so-and-so has a combine willing to rent it out.”

Michele first became interested in flour health when learning about how a healthy soil biology can help the environment. With their kids in the same class at school, Michele met Phil Taylor of MadAg and began attending local MadAg chapter meetings where she learned that the city [then] didn’t have a mill. This planted a seed in the mom-of-three.

Because larger equipment requires space, Colorado really hasn’t had a farmer who grows heirloom grain at scale. Farmers grew wheat but used their own small-scale mills, like eight-inch or 10-inch mills, to mill their product and resell, or like Black Cat Farm, sell it to [its] restaurants.

[Read profile of Boulder-based nonprofit building a seedhouse of locally adapted seeds]

Michele’s mill includes two granite mill stones, 30 inches in diameter, which have a unique pattern cut into them. The stones slice the grain like scissors over and over, and centrifugal force pushes out flour. One of the driving forces in her purchasing the mill laid in the way it would benefit the whole chain, that farmer who needed a larger mill would have access to it.

“If you have growers but no one to process it,” says Michele, “it never develops as a product or a market.”

Town effort

“I think what needs to happen is whole consumer base — all the eaters, the chefs, the bakers — needs to understand role of flour in our diet,” says Michele. “So having more people talk about grain and having other millers is a good thing. As much as we want to be first to market, it’s about first creating a market.”

Michele, who previously practiced law and then investment banking on Wall Street came to Boulder with no agricultural background and experienced firsthand the power of Boulder’s local farm community.

While doing some trials for MadAg in 2019 on a different section of her land and having elk come and eat it all right before harvest, Michele needed help.

Farmer John Brown of Browns’ Farm, another local mentor, came over to till the soil — and teach Michele how to drive a tractor, Farmer John Ellis came over to turn the grassland after Michele hand-planted the seeds and then John Schlagel saw she had put the field in the wrong spot entirely and came to help with irrigation.

“Coming from Manhattan,” Michele says, “this is a different kind of support.”