Just north of downtown, near where Mapleton Avenue intersects 9th Street, water runs beneath the road, blocked off by cement and rebar, and closely guarded by leafy trees. I always stop and watch the water walking from my car to work.

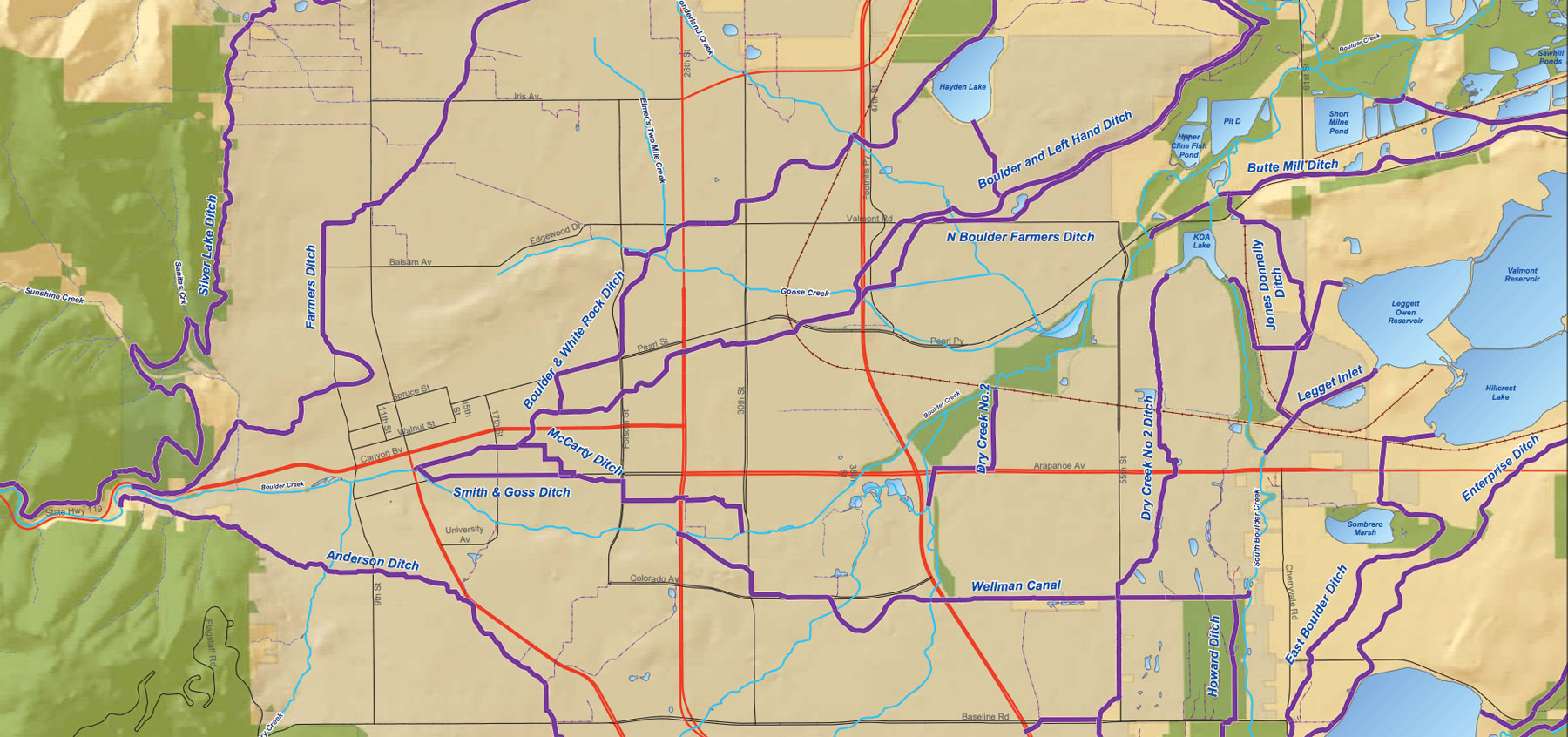

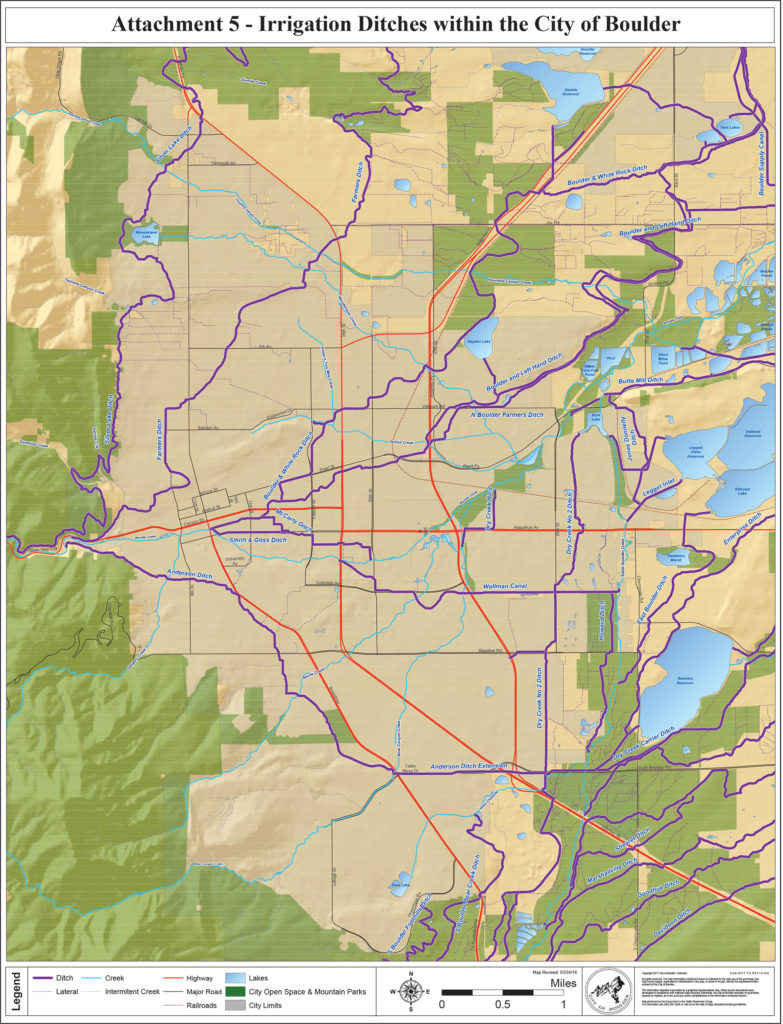

The little waterway is one of more than a dozen ditches shunted from Boulder-area creeks that provide water and irrigation to city and Boulder County, a practice implemented in the late 1800s and still flowing strong today.

Early Boulder settlers first started using irrigation ditches in 1862 to siphon off the water running in Boulder Creek for use in irrigation in the city’s eastern agricultural region, beginning with the Farmers Ditch shortly after Boulder opened its first schoolhouse at 15th and Walnut Street.

Ever since, these local waterways have been critical to Boulder’s agriculture and development.

These irrigation ditches provide water from natural water systems such as Boulder Creek and Left Hand Creek to farms all over Boulder County and beyond. Other sources include South Boulder Creek, Fourmile Canyon Creek, Dry Creek, and Saint Vrain Creek among some other smaller waterways (such as Rock Creek.)

The irrigation ditches provide Boulder’s municipal water supply system with water for treatment and delivery, and the city uses the natural ditch water to support local agriculture on its open space land and through its agricultural leasing program, as well as city parks. Roughly 30 percent of the city’s drinking water comes from irrigation ditch water.

Ditches normally flow from April through October, though some do run water in the winter to fill reservoirs. However, outdoors and left to nature’s whims, interception by surface and stormwater drainage can cause irrigation ditch flows to vary, along with fluctuation in supply and demand, with some ditches turning on or off with little notice.

Farmers Ditch, the waterway at 9th Street and Mapleton I watch on the way to work, begins at the kayak course on Boulder Creek just west of Eben G. Fine Park and then flows northwest to Boulder Reservoir.’

Farmers Ditch, the oldest ditch in Boulder, as it crosses 9th Street. Image: Tatyana Sharpton

Ditches + farming

Many of Boulder County’s farms and greenhouses still depend on ditch water to sustain their businesses, such as Esoterra Culinary Garden, located in a co-op farming space next to McCauley Family Farm on N. 63rd Street in Longmont.

Esoterra’s water comes from the Left Hand Ditch Company, which carries snowmelt from Left Hand Canyon. Believe it or not, the Left Hand Ditch Company owns the rights to the water in Lake Isabelle.

Natural water from ditches doesn’t have the added chemicals, like chlorine chloramine and chloride, that can exist in treated water and deplete the soil by stripping minerals, consequently killing plants, said Mark DeRespinis, who runs Esoterra Culinary Garden on land leased from McCauley Family Farm.

Estorra uses a drip irrigation system to water its crops but cannot count on ditch water year round; it sometimes runs dry.

Typically, Esoterra retrieves water from the ditch about a dozen times per season, or once every couple of weeks by lifting a gate on the ditch near the farm (often metal or wood, though sometimes a tarp) to release the flow. From there, a hydrostatic pump regulates the flow from the ditch to the drip system throughout the fields.

Crops the Left Hand Ditch water helps grow include Korean melons, Cucamelons, Sicilian Purple Cauliflower, and Bachelor’s Buttons, tiny purple European wildflowers that garnish dishes such as Corrida’s chickpea Cumin Panisse.

Quite a bit of Boulder County open space is used for grazing, as well as growing alfalfa and hay. This land is often leased, and the tenants grow, harvest and sell the crops and sometimes graze livestock. The majority of this pasture land is maintained by flood irrigation, through laterals (smaller ditches) that break off from main ditches is sometimes use to irrigate these vast spaces.

Ditch ownership

Unlike streams — for which they can sometimes be mistaken — where the flow occurs naturally, the ditch’s flow of water is controlled by a private nonprofit ditch company. Typically, these nonprofits have shareholders who pay a fee to support ditch operations and maintenance. The amount of water received is in proportion to the shareholder’s shares in the ditch company.

Boulder County’s 2018 Ditch and Reservoir Directory lists approximately 166 private nonprofit ditches and reservoirs in all of Boulder County. Boulder City alone houses 17 of these within its city limits. Today, City of Boulder is a shareholder in more than 30 different ditch companies.

There are about 10 or 12 ditch companies working with these 17 ditches, and some of them don’t belong to an actual company but are overseen by tenants in common, meaning the owners of the property work together to maintain the ditch.

While ditch companies typically own the irrigation ditches, the land surrounding the water rarely belongs to these companies. Instead, they have a “prescriptive easement,” which give access to operate and maintain the ditch. In addition to delivering water to its shareholders, the ditch company’s main responsibility is to maintain and operate the ditch.

Most of these companies are operated by a voluntary board of directors who make decisions on behalf of the interests of the other shareholders in the ditch. In Boulder, city staff who serve on these boards often work in either the Public Works or Open Space and Mountain Parks Departments.

Often, the prescriptive easements that ditch companies own go back to the original construction of the ditch and predate current property ownership. And since rarely are the easements recorded in public records and don’t come up in a property title search, property owners may be surprised to learn their property has a ditch easement.

Header image: Boulder ditch map. Source: City of Boulder