Legit tears were something I did not expect when I dropped by the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art to finish reporting this profile.

I was surprised but it happened.

The 47-year-old museum at 1750 13th Street next door to the Dushanbe Teahouse bustled with last-minute preparations as associates hustled protective plastic, space-checked paintings, and taped off sections for a temporary mural as I popped in to get a few photos for this profile and ask the museum’s executive director and chief curator David Dadone some final questions.

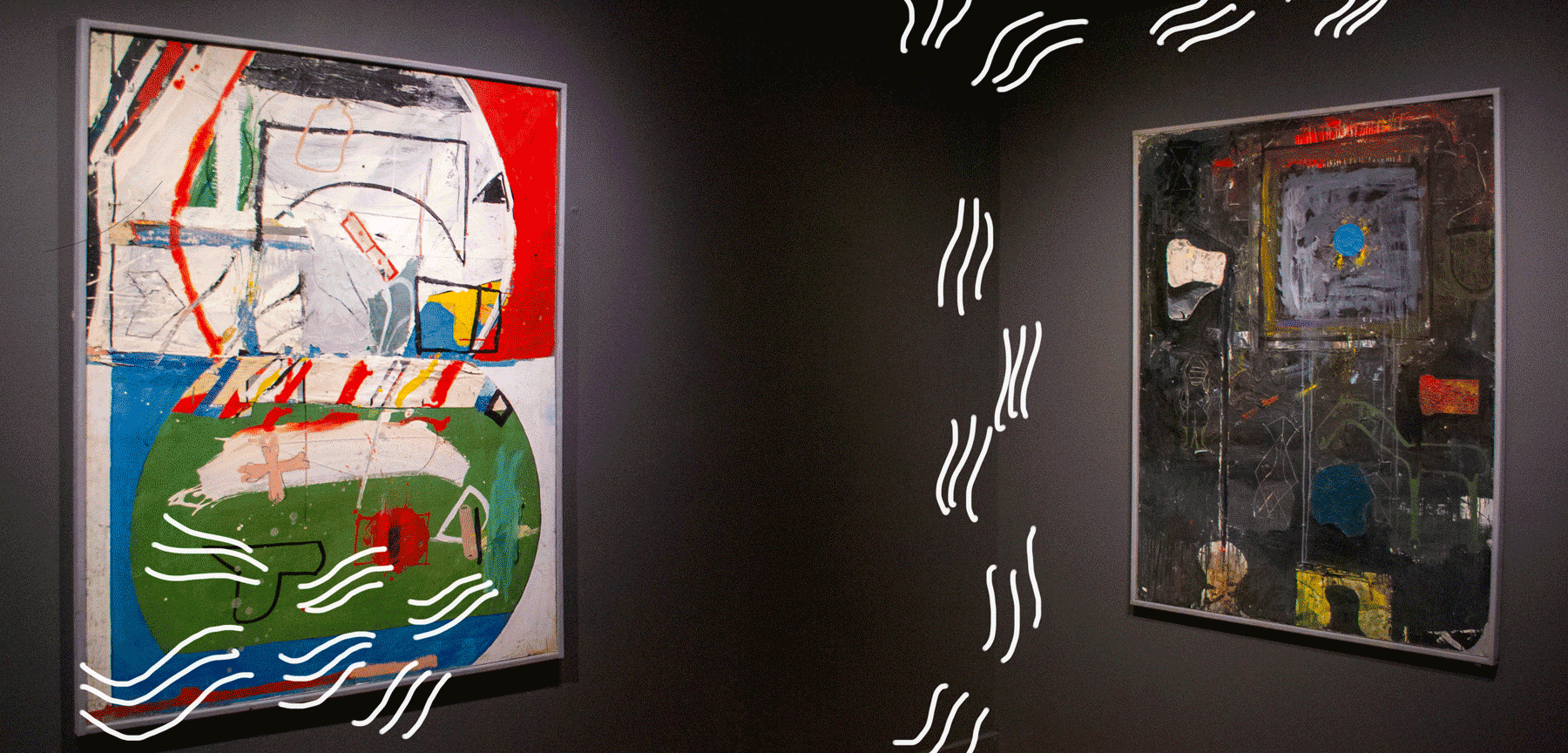

The exhibition they were preparing — “Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions” – opened on June 7; it showcases over 50 years of paintings, digital animation, installation art, and film by Denver-based artist Clark Richert.

The museum’s 47th show, the exhibit focuses on the marriage of art + physics and the exploration of dimensions and space. It will fill the space until Sept. 15 with a $2 general admission.

One of Clark Richert’s paintings at the current BMoCA exhibit. Photo: Taty Sharpton

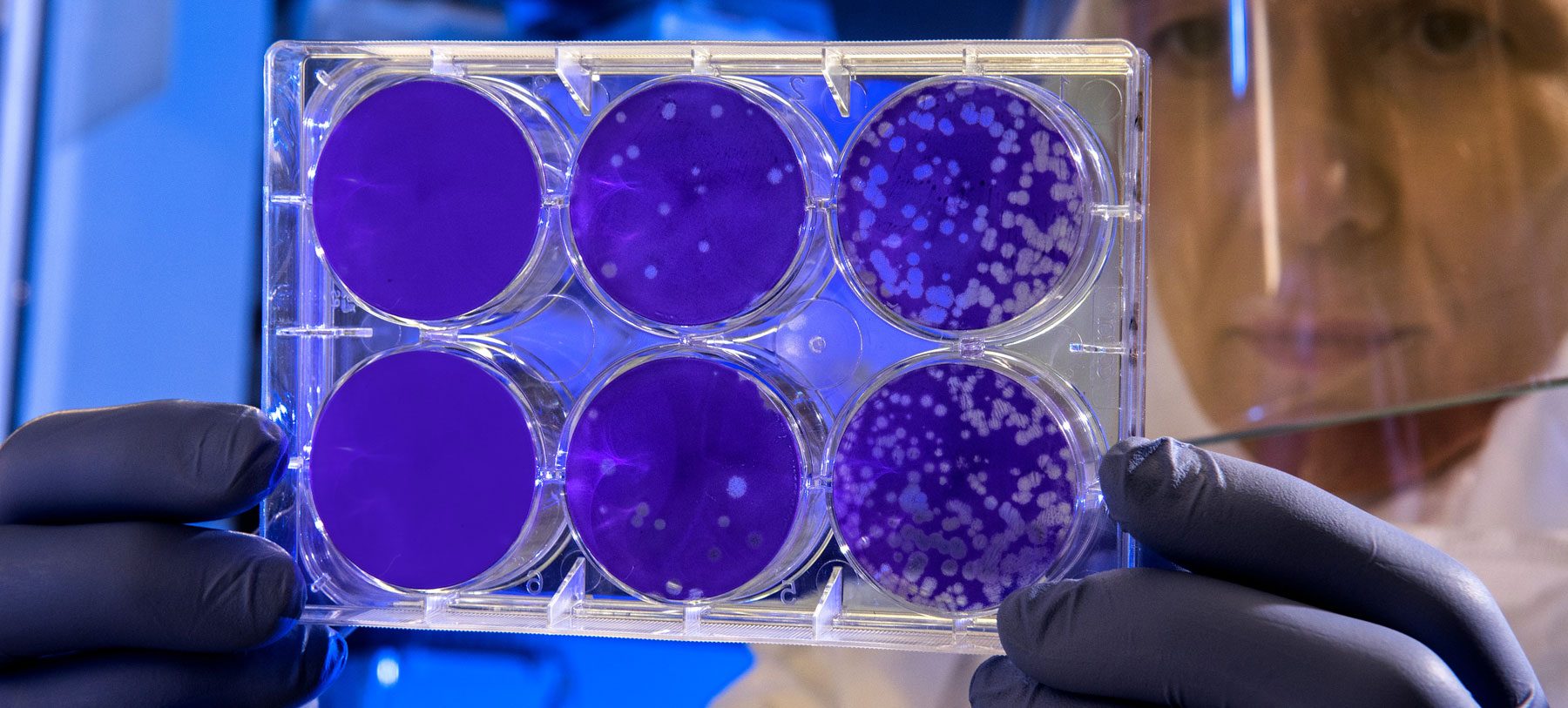

To add another dimension to the exhibit, BMoCA partnered with two CU science professors to discuss the exhibit in the context of their specialties: quantum physics and outer space.

Dr. Erica Ellingson, from the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, and Dr. Steve Nerem, from the Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences, will speak Friday, Sept. 6 from 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. in an event titled, “When the Stars Align: Painting and Physics.”

This cross-disciplinary dialogue is a foundational element of BMoCA’s mission. By facilitating explorations of art through unique perspectives – such as physics, in this case, or botany — the museum aims to inspire a deeper appreciation of art in visitors.

Looking to center

Originally called the Boulder Arts Center, BMoCA got its start when a group of local artists founded the space in 1972 in the spirit of a Kunsthalle – a museum that does not keep a permanent collection, instead focusing on hosting visiting exhibits.

Over the years, its scope widened and the space evolved into the museum it is today, offering several exhibitions each year as well as a variety of programs and educational classes, both onsite and in collaboration with other institutions.

In 2012, the city of Boulder decided to reshape the civic center — from 9th Street to 14th Street between Arapahoe Avenue and Canyon Boulevard.

The Museum saw this as an opportunity to expand. It wants to purchase the building currently just behind it and expand into a full blown institution with classes, events and more exhibits.

The museum is currently raising funds for the capital project. It needs to raise $1 million to receive a matching amount of a voter-approved city initiative to support nonprofits with capital projects.

The aesthetics of information

A fresh paint smell still permeated the gallery rooms four days before the exhibition’s opening.

Museum executive director David Dadone led me through the maze of rooms that would house the various parts of the exhibit, up the stairs past the area that houses his office and into a small conference room where several of the exhibit’s large paintings awaited hanging.

I found the exhibit sneak-peak thrilling, but also the art genuinely moved me.

In this exhibit, BMoCA dives straight into the heart of one of the most stimulating eras of art-making, the mid-60s and 70s, where mediating materials with information created new spaces for artists to explore.

Richert’s paintings overwhelmed me. The work feels fresh and current – even though done over the span of 50 years.

Color, movement, and decisiveness of each piece’s form and mark gave weight to every detail.

“I don’t want my paintings to be pretty,” Richert told the crowd at the exhibit’s opening reception on June 6.

From a family of scientists, Richert has a systematic art process, often deriving his compositions from five-fold symmetry and the scientific Munsell system of color, which defines three characteristics for each color: hue, value (its lightness or darkness) and chroma (its purity – colors with lower chroma appear more pastel, for example).

“There are no ugly colors,” Richert says, “every color is created equal … except permanent green light.” He points to a small green square in the corner of the large-scale painting of pink and purple toned molecular compounds behind him.

Interestingly enough, this square is what made me cry.

The collection of ranges from abstract expressionism to massive hand-painted tessellations and all-over compositions to a clean-cut visual plans for Drop City — the artist collective he and several others started in Trinidad, Colorado, in 1965.

Art as catalyst

“We try to bring in unique programs and find the edge of how can we mediate between information and understanding,” David says. “Spark a conversation. Art can be a catalyst for understanding anything.”

BMoCA, like BLDRfly, strives to foster a genuine conversation with its work. “Our job isn’t just to represent local artists but to present Boulder with new brilliant dialogue and discourse,” David says.

The mission is twofold: keep Boulder plugged into what’s happening in the outside art world and to create a space where the city can better understand and harness its creative energy.

Feature Image photo + illustration: Taty Sharpton