Boulder’s outstanding city design shines as a national example of smart growth.

Beautiful cities don’t happen by accident, and Boulder offers perhaps the nation’s most successful story of civic design, highlighted by its greenspace trifecta: the vast amounts of city-owned land that effectively prohibit sprawl; the “blue line” that prevents buildings creeping up the mountains; and the 55-foot building height limit (chosen to match the height of the city’s tallest cottonwood trees).

Other cities blessed with exceptional natural beauty, such as Austin, Texas, where Boulder’s new director of Planning, Housing and Sustainability Jim Robertson, 62, called home before moving to Boulder in August 2016 for his short stint as the city’s Chief Urban Designer and assuming his current position this August, could have used a similar city design.

Austin — where Robertson lived and worked for 25 years — used to be a natural oasis; now strip malls and developments stretch nonstop from city limits deep into the rolling Hill Country west of town, adding a choking claustrophobia to area life.

While it provides beauty, access and expansion in all senses of the word, and prohibits the constriction cities such as Austin face, Boulder’s stunning, vast amounts of greenspace and height limits also presents significant civic design challenges. Talk to any longtime Boulder resident about the city’s trajectory, and a recognition that Boulder is rapidly Aspenizing — becoming a high-priced, tony environment fit primarily for affluent residents —likely emerges.

Robertson faces this challenge, and others, as one of the key steward’s of Boulder’s growth as the city’s highest-ranking civic planner. “There are often no easy answers as we strive to reconcile the city’s different values,” Robertson says.

A beautiful ride

Earlier on the morning Robertson and I spoke in mid August, he and his wife rode from their home in south Boulder, traveled down Marshall Road, crossed over Highway 36 on Cherryvale Road and road back home as the sun rose illuminating a beautiful Flatiron view.

Robertson’s ride to Boulder was just as satisfying.

He started his career in law, but felt pulled to do work with more tangible results. “Work life should be more meaningful,” Robertson says of his pull toward civic design.

After going back to school to get a master’s degree in architecture, he got a job with an Austin architecture firm in 1996 where he remained until 2006 when the itch to push deeper into civic design led him to work for the city of Austin.

Sign up for BLDRfly's newsletter

“I’m fascinated by cities, how they work, why they work, what happens when they don’t work,” Robertson says.

He worked as an urban designer for Austin from 2006 until his move to Boulder last year.

With the city of Austin he played a role in revitalizing downtown, which was as an after-work hours ghost town before a major mid-Aught revitalization project.

That project successfully brought together the elements that make a city dynamic: economics, hotels, housing and homelessness, parks and recreation, arts and music, Robertson says. Austin now has one of the nation’s most vibrant downtowns.

Boulder, and Robertson, are striving to do the same for Boulder.

Boulder’s heart

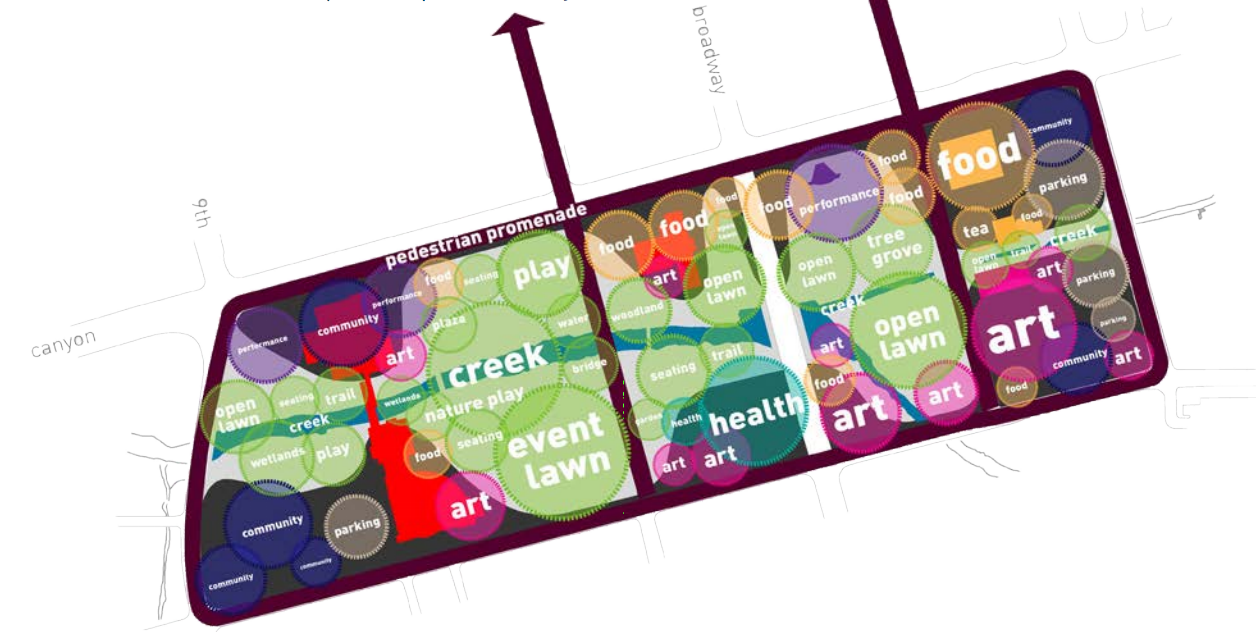

One of Boulder’s projects central to Robertson’s heart now is the Civic Area, the area surrounding Boulder Creek from 9th to 14th streets between Arapahoe Avenue and Canyon Boulevard.

It’s the heart of Boulder, and has not lived up to its potential, Robertson says.

It has the core features of a dynamic, vibrant area — the downtown public library, vast open grass lawns, the tea house, the museum of contemporary art, the seasonal Boulder County Farmer’s Market — and the city has a plan to polish and add to them to make the area really shine.

The Civic Area Master Plan, which Boulder City Council adopted in 2015, will guide the area’s development. The design includes a “state-of-the-art nature play” area on the south side of the creek, with arts and culture on the west end (where the public library is) and “food and innovation” and possibly a public market on the east bookend.

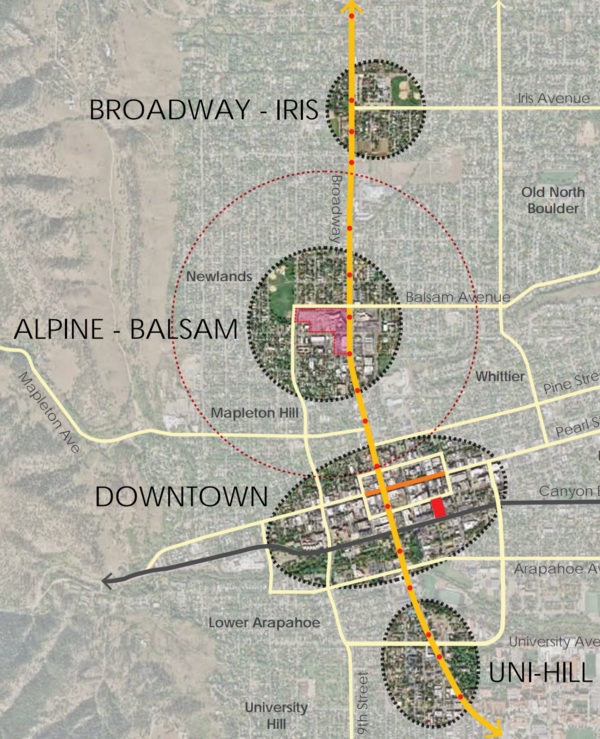

Phase one of the master plan — the major work that has gone on for nearly a year on the north side of Boulder Creek between 9th Street and Broadway — is just the tip of the iceberg, Robertson says. It’s part of a larger plan to connect Boulder’s west end along a north-south civic path: the Central Broadway Design Corridor.

The new 11th Street pedestrian bridge over Boulder Creek is called the 11th Street Spine for a reason — it’s meant to shunt the city’s energy (and people) between University Hill and downtown, and serve as one of the connectors to facilitate flow further north to the emerging Alpine-Balsam development on the 8.8-acre former Boulder Community Health site the city purchased in 2015 for $40 million and the Iris and Broadway site, where the county owns land and may offer a promising site for civic development. The latter sites offer promising areas for public-private development.

Robertson sees the Civic Area’s future potential as a vibrant stew of public and private activities, possibly including a new city hall building; the current building stands at the corner of Broadway and Canyon Boulevard.

The Civic Area plan, and the larger Central Broadway plan, include a focus on building equitable, affordable housing and public spaces. We’ll be following how that plan pans out.