In this high desert, water is one of the area’s most valuable resources: for development, agriculture and more.

Nearly every year for the last twenty years, Boulder County has experienced drought to some degree. With 99 percent of Colorado in drought this summer, and Governor Polis officially adding Boulder County to the Colorado Drought Mitigation and Response Plan last week, water is more important than ever.

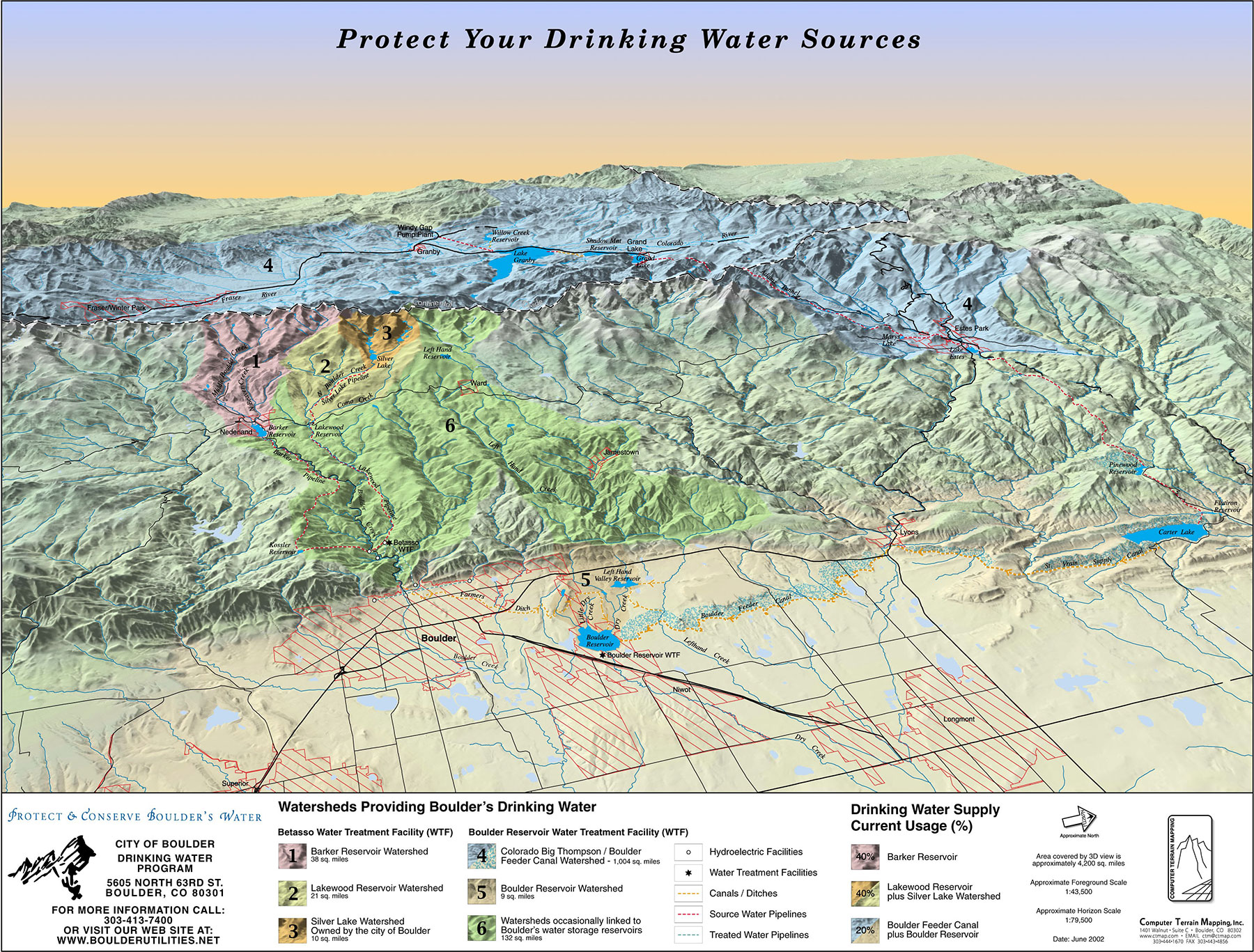

Boulder’s water comes primarily from two sources: the North Boulder Creek Watershed and Barker Reservoir just below Nederland, with the majority coming from annual snowfall that melts and either diverts from the streams into pipelines or fills up the reservoirs for dry seasons.

40 percent of Boulder’s water has come from the watershed that starts at the Arapaho Glacier, an alpine glacier off the peak to peak highway above the Rainbow Lakes and just east of the Continental Divide, and the largest glacier in Colorado.

Another 40 percent comes from Middle Boulder Creek via Ned’s Barker Meadows Reservoir, and the remaining 20 percent comes from the lakes of Colorado’s Western Slope by way of the Colorado-Big Thompson diversion, a federal water diversion project in Colorado designed to collect Colorado River water and shunt it from the western slope to the Front Range and plains.

Boulder first acquired land in the North Boulder Creek watershed in the early 1920’s when it acquired Silver Lake Watershed shortly after discovering Arapahoe Glacier in the area.

Because of Boulder’s semi-arid climate, the amount of water the valley has varies year to year based on the snowfall and rain. Due to this, the city has developed its water supply and water rights systems with the understanding that Boulder varies between wet and dry.

In wet years, the city has more water than it needs and it gets stored in Boulder’s reservoirs. In dryer years, when the streams don’t have enough physical supply to meet everyone’s demands; the city relies on water it puts in storage, with that amount depending on the dryness of that year and prior snowmelt.

In times of extreme dryness, like this year’s arid summer that brought on Colorado’s wildfires, the city prioritizes providing water to meet essential needs, such as indoor water or firefighting.

“The way we do our water supply planning, we don’t have a number that says how long our supply will last,” says Kim Hutton, a water resources engineer at the City of Boulder. “If it’s getting dry enough that we start using water from reservoirs and it’s getting lower and lower, we implement water use restrictions. There’s not even enough water to irrigate trees in a really dry year.”

Who has rights?

“Nobody owns the water,” says Blake Cooper, a Boulder County Resources Manager. “You can’t pump it.”

While Colorado views water as a public resource that cannot be owned, individuals and organizations can take water out of a stream if they have a water rights decree, which allows them access to a certain amount of water depending on the underwriting of their water right.

Formalized in the 1870’s, Boulder’s water rights infrastructure operates on a priority-based system giving top priority to senior water shareholders, such as those who have had their rights since 1870 (think, old farm families). This means in dyer seasons, the amount of water that people who received water rights in more recent years, like 2020, can take also dry up.

Individuals can acquire water rights through an application process.

Colorado law also states that nobody can waste water; all water siphoned from streams must have a beneficial use, such as for agriculture or drinking water (also known as municipal or domestic water.)

“When you apply for a water right,” Kim tells us, “you have to say where you’re taking water (point of diversion), where you’re going to use it and what for. Then the state’s Division of Water Resources tells you how much you can divert from the creek — which is usually a flow rate, volume per second.”

When the creek has a certain amount of water flowing through it, the state will give whoever has senior water rights to that creek dibs, followed by the next and so on, while the creek still has water. Water rights also differ depending on whether the holder plans on using the water immediately or storing it for later use, where a volume limit falls into play.

Typically, the most senior water rights in Boulder, Kim tells us, pertained to agricultural water rights with many early Coloradoans living on farms and drawing water through a well. Once the towns began developing, the cities added municipal water rights to supply to the people, but this began about ten to fifteen years later than the initial agricultural water rights.

Boulder County owns water rights to 13 reservoirs and has facilitated more than 57 directly held water rights, and the city also has an agricultural water leasing program, which helps it manage year-to-year supply variation in average or high supply years. Additionally, people can also have access to water via stocks held through private ditch companies.

Farmland + ditches

Boulder’s water feeds not only its human and animal residents but also its plants and agricultural lands. Native crops like alfalfa, beans, corn, sugar beets, grains and vegetables require anywhere from 1.5 to three acre feet, or 326,000 gallons, of water alone.

[Read about Boulder’s Constellation of Ditches]

To keep up with its early irrigation and agricultural demands (and now approximate 25,000 acres of productive agricultural farmland), the county dug ditches in the 1860’s, 70’s and 80’s to spread water from its creeks across the land.

These ditches still exist, operated by private ditch companies. To fund the ditch operations, those who originally dug the ditches sold stocks in their companies, which allowed holders access to a certain percentage of water that would run through that ditch. Ditch companies have water rights and shareholders’ stocks give them access to it depending on the stock’s size.

In some cases along the Front Range, Colorado’s cities have acquired or purchased some of the stocks in ditch companies, which give them access to some of the most senior agricultural water rights. Such acquisitions can happen, for example, when a Boulder farmer sells his land to developers to build houses; in those cases, the City of Boulder would buy the water rights. Currently, Boulder owns water rights to 61 incorporated ditches and 31 unincorporated ditches.

Although the water in ditches was initially decreed for irrigation and agricultural use only, users can appeal to Colorado’s Water Court to amend the water right to add additional uses, such as domestic, or drinking, water, just for that fraction it owns.

Ditches normally flow from April through October, though some do run water in the winter to fill reservoirs. However, interception by surface and storm water drainage can cause irrigation ditch flows to vary, along with fluctuation in supply and demand.

The downside to publicly owned water comes when the moving parts and multiple players don’t line up, causing riffs in communication and ditches turning off with little to no notice, such as this August when most of Boulder’s ditches turned off temporarily.

“Nobody told us anything,” says Amanda, co-owner of 63rd Street Farm, who received a call the Friday before from the city’s Open Space & Mountain Parks department saying it may happen and a contradicting message from her ditch rider saying it wouldn’t. “They just shut them down.”

The water shutdown put many Boulder farmers in panic, with the season’s end looming just as it peaked, but luckily water came back on a week later. After speaking to the State’s water commissioner, Amanda learned that due to the heat and lack of rain, the snow melted too quickly and came all at once, and the shut off occurred because there wasn’t enough water in the creek to supply all the water rights.

Header Image: Ned’s Barker Meadows Reservoir. Image: Tatyana Sharpton.