The Boulder community got quite a startle when a mountain lion trapped itself in a two-story home in central Boulder last Thursday night, August 9, apparently after a house cat.

The resident called police just before 11 p.m. after coming upon the lion at the home in the 400 block of Marine Street near the base of Flagstaff Mountain. Police found the house cat dead and a mountain lion trapped inside.

Police and wildlife officials scared it out of the house after an hour. Police think the lion pushed in through a screen and couldn’t get out again.

Video of the mountain lion stuck in the Boulder house last Thursday.

The close encounter, and others recently reported in Boulder in recent weeks, begs the question: What’s up with mountain lions — also called pumas and cougars — in Boulder?

BLDRfly dug deeper to find out.

It turns out the Front Range at 4.1 adult lions per 100 square kilometers (38.6 square miles) has one of the highest density of lions of any region in the U.S., according to Mat Alldredge, a mammals researcher with Colorado Parks and Wildlife and one of three co-authors of a new report that reveals findings of a multi-year Front Range mountain lion study.

The more typical range in similar areas of prime lion habitat like the Front Range — marked by lots of prey, low hunting pressure and pine, juniper and oak brush wildland — is around 3 lions per 100 square kilometers, Alldredge says.

The new report is part of a years-long Front Range Mountain Lion study, which looked at human-lion interactions from I-70 to Lyons and north-south foothills to 15 kilometers west of the Front Range foothills, a fitting mission given the house visit a puma gave a Boulder household last week.

The study’s total range spanned 900 square kilometers, but we can’t simply multiply 4.1 by nine to get total adult area lion count, as the model accounts for some overlap, Alldredge says. But it’s safe to say that the number of Front Range adult cougars measures in the dozens.

Why so dense here?

Mountain lions face fear when interacting with humans in all environments including residential areas such as Boulder. But hunger draws them in, as does easy access to prey such as human-adjacent animals like racoons and house pets and, in some cases, squeezed by dominant lions deeper in the mountains, Alldredge says.

One of the key reasons for high-density mountain lion Front Range presence in Boulder and Jefferson counties has to do with the greater amount of private property here.

Further north there are larger expanses of public land, which makes dog-based cougar hunting — the predominant way to hunt big cats — more feasible. In Boulder County (and Jefferson County), private property is much more prevalent, blocking extended dog hunts.

Lions here have a bit of space free from hunting pressure.

They also find food. In the Boulder area, the study showed, area lions have some of the highest uses of alternative prey such as raccoons, rabbits, house pets and other four-legged creatures not among their core prey of mule deer and elk, Alldredge adds.

Humans contribute here as they tend to maintain yards with lush landscaping, which offers cover and forage for cougar prey.

In fact, Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials are aiming to capture what is thought to be two lions getting bolder in Boulder.

When are lions prevalent in Boulder?

There’s a bit of seasonality to mountain lion presence in Boulder.

Their city presence typically peaks in late spring, early summer, at a time when lions are used to hunting smaller prey as fawns and other young still struggle to gather their adult legs.

Lions are most active dusk to dawn in residential areas, just as they are in the wild.

Boulder’s lion population

Boulder’s lions are native, as they are in many places where they’re still found. They had the widest geographic dispersals of any mammal other than man in North America before being squeezed into current wildlands by human civilization, Alldredge says.

Adults are usually here to stay, he says, but youngsters can drift in and out. They also tend to be ones seen in town as they are squeezed out from territory deeper into the mountains patrolled by adults.

Male and female adults live separately, over separate territories, coming together to mate briefly and then separating. A with most mammals, females raise the young.

Dominant males have home ranges that typically span from 500 to 700 square kilometers, roughly the equivalent of the Front Range from Boulder Canyon south to Coal Creek. Adult females have smaller home ranges — 90 to 110 square kilometers.

Young lions stay with their mother for up to 18 months; as they grow up females typically stay nearby, males can wander farther in search of territory, food and mates.

One area lion tagged in the study went to Kansas before settling in New Mexico over the course of a couple months, ultimately meeting its end by hunter there.

How lions were detected in study

The study measured mountain lion population by measuring the marked and unmarked cats that hit a camera trap after called in with simulated prey calls.

Researchers then used statistical models to extrapolate an area-wide population, Alldredge says.

How to mitigate lion presence

Wildlife officials have some simple recommendations to help keep cougars away from your home, including:

- Use motion-sensor lights around your home

- Don’t leave pet food out

- Minimize landscape features that enable hiding

- Keep pets under control

- Leave doors closed when not at home

- Teach kids to be aware of lions, avoid playing unaccompanied from dusk to dawn.

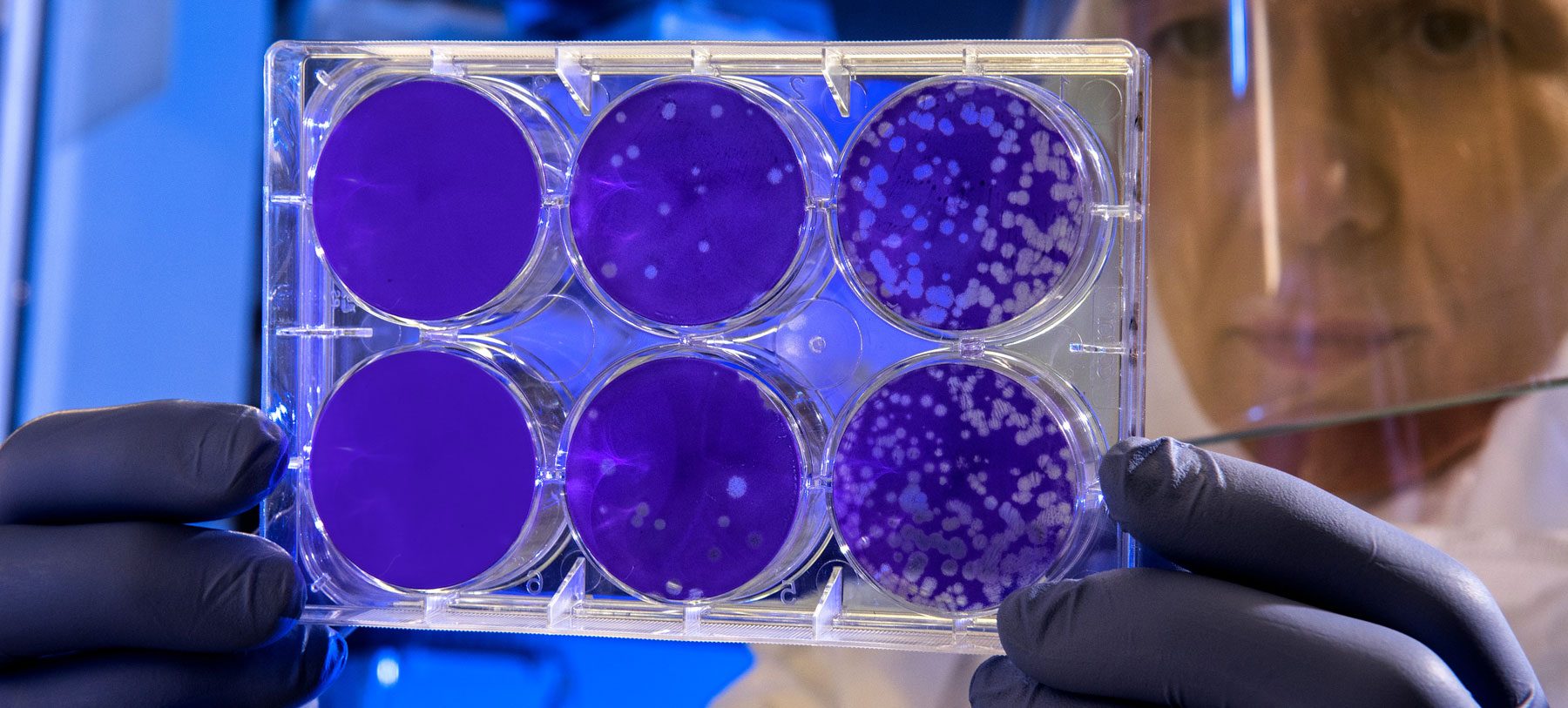

Feature image: Front Range mountain lion. Photo: Courtesy of Colorado Parks and Wildlife.