Editor’s note: This is part three of a two-week backcountry Alaska ski adventure by BLDRfly writer Marc Doherty earlier this year. Read part one here and part two here.

Our first morning in the RV and I awake in a queen-size bed and an accordion curtain protecting my eyes from the panorama of blinding white outside the window. I pull back the curtain. This is the day I check “Skiing in Alaska” off my list.

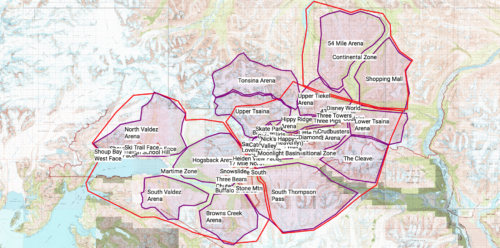

After breakfast burritos and cups of coffee, we gather our familiar gear: avalanche beacon, shovel, probe, two-way radio, first aid kit, skis, climbing skins, helmet, poles, ice axe. An hour later we head into the Crudbusters arena, our “warm-up” zone.

The sunny morning pairs well with the crisp in the air. Clicking into our skis, we skin across the Tsina River on a bridge and continue on crusty, refrozen trailhead snow. We begin a trek up, with the Trans-Alaskan pipeline buried beneath our feet.

After a three-hour slog, we reach the glacier at the base of the line we want to fly and excitement jumps through the roof. We stuff our mouths with watermelon Sour Patch Kids to keep the buzz flying, chose our couloir and go.

Skis on back, ice axes in hand, we bootpack up the 40-degree face. On our way, we encounter a wide variety of snow. The first thirty feet is shin-deep powder, the good stuff, the next fifty is bulletproof, wind-packed crust. This isn’t the consistent powder we dreamed of; the conditions are, shall we say … variable.

Topping out, we find our perch. Keegan drops first. The first two turns show glory. The next, however, sounds like chattery hell. It becomes clear that we must throw away the dream of top-to-bottom powder and just have fun.

After watching everyone milk those first two turns, I drop last. Excitement and peace, two emotions always present before setting down a challenging line, pump through me. This time, however, there’s something more. There’s a monumental vibe to it. Not for the conditions or the line’s difficulty, but because of the all-consuming feeling of this as a landmark moment in my life.

First line

I enjoy the brief flotation of the top turns and settle in to the technical chattery turns for the rest of the line. As I reach the apron, the area below the rocky walls that confined me above, I rest.

I came to Alaska to ski fast, so I decide to straightline to my friends waiting at the bottom. No turns, pure speed, screw variable conditions. When it’s time to pump the brakes, the bumpy and firm sastrugi stops this runaway train.

Falling never felt so good!

We make our way back to the RV down firm and frozen slopes. The sky has grayed during our five-hour adventure, and we march back to the camper in a subdued light.

Waves of accomplishment and excitement at more days to come wash over us, and mix with the stink-steam pouring out of our still-warm boots.

The next few days we settle into RV life and, so too, do low-hanging clouds. We’re officially “socked in” but the atmosphere appears not able to wring any measurable moisture from the clouds and bestow us with the soft, fluffy powder of our wet dreams.

Sign up for BLDRfly's newsletter

Our mornings grow longer. Two pots of coffee turn into four and novels replace the guidebook in our hands. We ski everyday, exploring new arenas, poking our heads up couloirs that don’t want to be skied and arguing about where the good conditions are hiding.

Late one afternoon after a few days of frustrated, chatterbox skiing, we decide on dinner at the Rendezvous Heli-skiing Lodge down the pass. Stinking of sweat embossed with minor notes of defeat, we eat, shower, reconnect and meet the residents.

A guide swings by our booth with a beer in hand and a grin on his face. His nose is Rudolph red and he emits a wholesome, blissed-out ski bum vibe. He shares the lowdown on area weather patterns, dropping some beta on where the good skiing may be. We listen intently, dreaming of our big break.

Dreaming of Pow, eating burgers + variable conditions

Variable turns out to be everyone’s word of choice to describe conditions around here, whether flying to the fun, or climbing to it.

Back on the pass and warmed by a roadside fire later that night, we catch the steady, slightly green haze of the northern lights on the north side of the road. Hazy and cloud-like, they flutter by overhead, some like a barcode scan laser, others like the fastest clouds you’ll ever see. Another reminder that I am on the top of the world.

The next day, in need of water and a sit-down meal, we head 30 miles down the pass to Valdez. At Keegan’s recommendation, we stop at the Old Town Diner for some enormous burgers. The diner interior is furnished with mostly outdoor furniture, but kept so clean it could be the patio showroom at Walmart. We down the burgers and curly fries and wash them down with Pepsi.

Valdez harbor. Photo credit: Marc Doherty, BLDRfly.

Our server is a short, portly man with a orange tie-dye shirt, paisley bandana, a mouth with only two front teeth and a smile so big his eyes close. Knowing that Valdez waters are famous for Halibut, we ask our server about fishing charters. He tells us it’s too early in the season for fishing, but regales us with his best fishing stories. His excitement teases our thirst for fresh powder.

After dinner, we walk the harbor. The air is calm. The water a still, dark, murky emerald. Snow-covered and skiable peaks surround the harbor.

A legend offers hope

While picking up Jeff, a late-joining member of our crew, at the Valdez airport we run into skiing legend Dean Cummings who pioneered backcountry skiing of the peaks surrounding Valdez with the late, great Doug Coombs. Our jaws collectively drop.

We find Dean at H20 Guides, his heli-ski operation. A solid 5 feet 9 inches with an intense jawline and piercing, analytical eyes, he stands in front of the desk. He measures each of us with his eyes as we shake hands. We give him the lowdown on our trip and he immediately probes us, asking about our qualifications and experience.

Dean Cummings.

Appearing to pass his test, Dean turns around and grab a pen and scrap paper. As he hastily sketches the geography surrounding Valdez, he describes the area’s various microclimates.

This five-minute doodle and explanation is the culmination of Dean’s life work; he has spent more time than anyone exploring and understanding the mountains here.

It becomes clear: to ski the snow we want, we have to fly. We ask Dean if he will drop us off for a day or two at one of the distant powder zones. He begins crunching numbers and, simultaneously, devising a new plan for us.

He explains his business, why it’s the best and where he sees it going. He explains that more and more people show up in Valdez wanting the human-powered adventure that drives us. He clearly wants a piece of that action and offers us a discount to join his guide school and help him expand his operations. A flattering and enticing offer, our imaginations take a brief flight.

Upon goodbye, he pushes open the exit door to the runway and mutters a warning: “Coombs and I almost died so many times in these mountains.”

After a dinner at comfort food haven Mike’s Palace, we head back to our home on the pass. Nearing the top of the pass, clouds grow and rain spits onto the windshield. It takes us all an extra second to realize what this could mean.

Rain here means snow up there!

We become meteorologists, translating wind direction according to the microclimate model Dean described. We debate for hours on how much snow this could be, where it could be falling and where we should ski tomorrow.

We dance and dance, poking our heads outside the RV door to make sure water is still falling from the sky.