Boulder has a rich legacy of homebrewing. Charlie Papazian, a homebrewer himself, founded what has become the rich art of homemade beer and craft brew in Boulder.

In 1978, Charlie founded the American Homebrew Association and subsequently published “The Joy of Homebrewing,” which has become a bible for the culture in town and nationwide. And now I’ve jumped on the bandwagon.

Since moving to Boulder during the pandemic, I’ve met several homebrewers, for one, my roommate Sean.

As we navigated a more locked-down world, we began trying out creating a Two Hearted Ale-adjacent beer in our backyard on a Tuesday afternoon in August after a trip to Boulder Fermentation Supply.

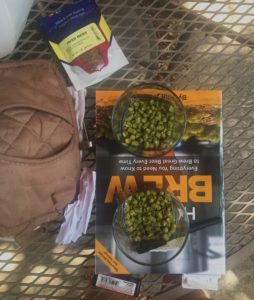

At Boulder Fermentation Supply, Sean and I ground 13 pounds of US Pale 2-Row malt and 8 ounces of Briess caramel for flavor. We bought the beer’s hops, White Labs’ WLP001 California ale yeast and siphon tubing to transfer the beer from container to container.

In a process called “striking the mash,” Sean stirs the first dose of US Pale 2-Row malt and caramel into 170 degree water in an Igloo cooler.

At the bottom of the Igloo barrel, a plate-shaped colander strains out malt sediment. After striking, Sean pours the cooler’s contents from the spigot below the colander until they’re clear of sediment.

Another round of near-boiling water heats in the pot for “vourlouf,” which means “recirculation” in German. We add the water, known as the “sparging” liquid, to the Igloo cooler. The resulting wort, a brownish orangish liquid that resembles apple cider, goes back into the pot.

Sean tells me to grab two pennies to toss into the pot so it won’t boil over. I say that I simply don’t believe him, but do it anyway for good luck. After a violent boil, the top layer of foam disappears and the brew breaks to a clear boil.

I set a one-hour timer to boil off 1.5 of the seven gallons in the brew pot. After 15 minutes, we add the first round of hops, the second after a half hour. Green bubbles froth to the top both times, emitting the smell of Centennial hops. I crave beer at 1:30 in the afternoon, but I guess that’s not unheard of in a craft brewery, and college, town.

Sean adds a teaspoon of Irish moss to clarify the beer. Technically a seaweed, the negatively charged moss attracts positively charged proteins in the wort. As the beer cools, this combination forms clumps that either precipitate or settle at the bottom of the pot, leaving behind a clearer beer.

When the beer finishes boiling, as a dark sky warns of rain, we carry the pot just inside the garage door. We set a large coil inside the brew pot, connected to two plastic tubes. One tube attaches to the backyard hose, the other drains into the yard. As icy hose water runs through the coil, it attracts the boiled beer’s heat, spitting hot water through the discard end. In about 20 minutes, the beer cools from boiling to 64 degrees.

We siphon the liquid through a strainer and into a sanitized bucket, legitimately and ominously named the “fermentation chamber.” Before adding yeast, I pour a sample into a test tube for the original gravity reading. We’ll take the final gravity reading before bottling. The difference between the two numbers will tell us how much sugar the yeast consumed, and thus the beer’s ABV.

The fermentation chamber sits in our fermentation chamber (what I’m now calling a dark corner of the basement) for a week. Then Sean transfers the liquid into a carboy to leave behind sediment resting at the chamber’s bottom. He also adds dry hops, which affect flavor and aroma but not the beer’s bitterness, which comes from boiling oil out of the hops like we already did.

After another week in darkness, we carry the carboy upstairs and bottle its contents on the kitchen floor. Sean pours beer into dozens of our best glass bottles, which we’ve saved for months, then uses a sealer to cap them. The 49 bottles return to the basement for another week.

When the beer’s ready to drink, we pass two six packs to each of our neighbors, and crack some bottles for ourselves. It tastes exactly like you’d expect a Two Hearted Ale-inspired brew to — citruisy, with a little floral and pine, backed by malt — and Sean even made these sweet labels and named it Four Eyed Ale.

Get ready for Boulder’s next homegrown craft beer – Jess’s Juicy IPA.