On September 1, the Boulder City Council approved, by a vote of 8-1, recommendations from the Open Space and Mountain Parks (OSMP) board of trustees for a prairie dog management plan which includes lethal removal of prairie dogs from 100 to 200 acres each year from a designated project area of city-owned land in north Boulder, with a goal of total clearance. This marks a monumental move, as OSMP has rarely used lethal control for managing prairie dog numbers.

The council’s decision comes in the wake of a years-long dilemma as prairie dog populations have skyrocketed, and while protected and cute, they heavily hamper farming on both city and county land, as well as private property. The city will begin implementing its new management plan in 2021.

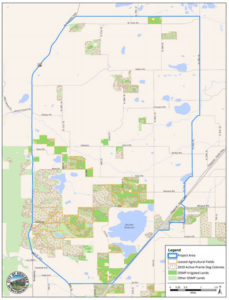

The prairie dog area in question exists on 967 acres in north Boulder, north of Jay Road and west of Diagonal Highway (see map below). The city has previously had a policy of relocating them, but efforts have proved expensive and not completely effective at keeping the prairie dog populations in check in the disputed area; the relocation program simply can’t keep up with the prairie dogs’ rate of spread into agricultural land. With the new vote, city workers will exterminate the prairie dogs by pumping carbon monoxide into their burrows.

Open Space has used the lethal option before, but not often. Between 2010 and 2018, Boulder County relocated only about 750 prairie dogs from OSMP irrigable agricultural lands, as the county prioritized other city and private-land prairie dog relocation needs over OSMP lands.

Currently, statistics show an estimated 132,000 prairie dogs on 4,457 acres of city-managed Open Space — the highest levels of prairie dog inhabitation since OSMP began tracking their occupation in 1996.

We provide more context to the issue in this article.

The Conflict

The city has acquired 16,400 acres of agricultural lands, including water rights associated with about 6,400 irrigable acres. As of 2020, it leases 78 percent of its irrigable land for agricultural uses. Because of prairie dog damage, over 1,200 acres of that (including 967 acres in the project area) fall at risk to no longer support an agricultural tenant, or have already seen abandonment in terms of use and maintenance of water rights.

The topic dances a tricky line, as prairie dogs have traditionally had protection via law on both private and public land in the city of Boulder. Additionally, most agricultural land neighbors public land, which prairie dogs often inhabit. This means that farmers can try to remove prairie dogs (not using lethal methods without a permit) on their lands but often see them crop back up due to close proximity.

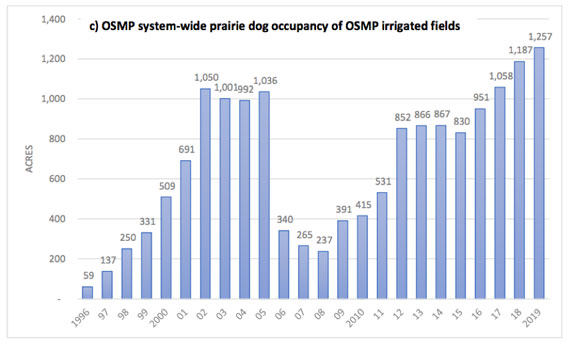

OSMP maps the extent of prairie dog colonies on its lands prior to winter each year, and while colonies occupied only 1,380 acres in 2009, they were found to have expanded to 4,153 acres in 2018 and 4,457-acres system-wide by 2019.

(Figure from: Management Review of OSMP Irrigated Agricultural Lands Overlapping with Prairie Dogs)

(Figure from: Management Review of OSMP Irrigated Agricultural Lands Overlapping with Prairie Dogs)

The area in question, irrigated agricultural land with the greatest number of agricultural tenants affected, contains about 2,400 acres of irrigated lands managed by OSMP — 967 acres of which prairie dogs occupy (about 43 percent of the irrigated land). The project area has over 2,000 acres of active colonies, with most (1,600 acres) of these colonies on unirrigated grasslands.

OSMP seeks to maintain ecologically viable prairie dog populations in the range of 800 to 3,137 acres and has established management designations on over 5,300 acres of city-managed Open Space where prairie dogs can live in protected status without removal except in unique circumstances.

Currently, 11 agricultural tenants now experience prairie dog conflicts on more than 19 percent of their leased, irrigable agricultural land, two tenants experiencing prairie dog occupation at the levels of 50 to 58 percent of their entire leasehold, making continued operation extremely difficult or not viable.

Prairie dogs

The black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) is native to the Colorado plains, or areas below 6,000 feet (if they drove little cars, they’d deserve a “Colorado Native” bumper sticker). They are one of five prairie dog species and once covered 7 million acres in Colorado, but now inhabit just 2 million acres in all of North America. Habitat loss and fragmentation, poisoning and recreational shooting have contributed to the decline.

Prairie dogs are diurnal (active during the day), burrowing rodents that reach almost 15 inches in length, including a 2.5-inch black-tipped tail, and usually live five to seven years. They do not hibernate and live in highly social coteries, or small groups within a prairie dog town, which typically consist of a breeding adult male, one to four breeding adult females, and their young offspring (less than two years old). When male offspring come of age, they typically disperse two to three kilometers km away from their colony to establish new territory and increase genetic diversity.

In Boulder and on OSMP land, prairie dogs tend to prefer short to mid-height grass prairies with non-rocky soils and mostly flat terrain. Although, they have been seen to live in less ideal areas due to development and encroachment.

They also primarily occur on edges of protected open space and as the colonies grow and deplete resources, they disperse to other areas. Since they live so close to urban areas while on Open Space land, they have been known to forage on landscaping, including people’s lawns and golf courses.

The black-tailed prairie dog is an “ecosystem regulator,” meaning that its presence affects a myriad of other ecosystem components: plant productivity, community dynamics, and nutrient cycling within an ecosystem.

As key components of their local ecosystems, when prairie dog populations leave an area, it can lead to a decline in available soil nutrients and the density of other vertebrates in the area. Approximately 170 vertebrate species rely, at least on some level, on prairie dog activity for survival, including: American badgers, bobcats, burrowing owls, coyotes, black-footed ferrets, golden eagles, and many others, according to Caldwell (2015).

The management challenge

Prairie dogs and their burrows are highly protected in Boulder by a number of plans and ordinances (Wildlife Protection Ordinance, Open Space and Mountain Parks Master Plan, The Grassland Ecosystem Management Plan, and the Agricultural Resources Management Plan to name a few).

Because relocation is expensive and often doesn’t completely work and lethal methods are heavily regulated, farmers and other landowners face a difficult challenge in regulating prairie dog populations that inhibit their use of Boulder County/City land. In many cases, they simply must abandon their agricultural lands to prairie dogs.

The typical transformation follows as such: as prairie dogs get in the way of haying equipment, farmers can initially transition hayfields to grazing land. Later, as populations and densities increase, irrigation of these lands becomes difficult to impossible.

Once prairie dogs fully occupy irrigated fields, all agricultural operations have to halt and that property is taken out of production. High population densities of prairie dogs on agricultural land can reduce crop yield, impact water ways, and lead to soil erosion. This is what has happened to much of the irrigated city-owned agriculture land.

An alternative to lethal control, suggested by non-wildlife managers, would be to keep prairie dogs in small, separated locations so they can’t create giant colonies that degrade the landscape or get in the way of new infrastructure. This effort has proved fruitless as isolated colonies struggle to survive and remain healthy, as they face limited breeding options and are more vulnerable to predation.

In urban areas, the prairie dog population density is often much higher (sometimes 250 times higher) than densities in unmanaged areas where they can move freely. Density has perhaps the most significant effect on the surrounding ecosystem; it can affect plant productivity and plant cover, determine the presence or absence of predator and commensal species, and the overall health of an ecosystem. In areas where colonies can expand naturally, densities occur at sustainable levels for the species and ecosystem.

The future

Prairie dogs, of course, will remain in Boulder, as the city will attempt to keep them in specific areas and discourage them in others. One thing is clear, starting in 2021, their impact on the 967 acres of OSMP covered in the new plan will diminish as the city implements lethal control.

Individuals still need to obtain a permit if they wish to use lethal control on their private lands, and the city’s use of this method is still limited to the project location described above. Any expansion of the project area will require planning and discussion by the city.